WATERFRONT FOR ALL 2025

Congratulations to the Seattle community on our beautiful, amazing, welcoming, waterfront. Special thanks to the multitudes who helped work for decades to get it built.

Learn more about how the state originally planned to build a new viaduct until Allied arts led a grassroots coalition to inspire a better vision: To create a waterfront for all!

ALLIED ARTS WATERFRONT MASTER VISION COLLABORATIVE:

LETTER FROM ALLIED ARTS

Fifty years ago, our civic leaders made a serious mistake. They cut off Seattle from its waterfront by building the Alaskan Way Viaduct. Now, the people of Seattle and the Northwest have an opportunity to correct this error and redirect the future of the region. We have the choice of giving future generations a vibrant Waterfront neighborhood, or cursing them with an even larger viaduct ripping through some of the most significant urban land in the Northwest.

Though removing the viaduct is the single most important step toward creating a great waterfront, planning and designing the surrounding neighborhood are also critical. Since the Nisqually Earthquake in 2001, public discussions have primarily focused on choosing a viaduct replacement and finding funding for it. Today’s leaders can leave a legacy by refocusing their attention on the societal and environmental benefits that a revitalized waterfront will give to generations to come. Ironically, 50 years from now, few people will criticize removing the viaduct or take issue with how much public funding was used to pay for the tunnel. Yet future generations will no doubt shake their heads in disbelief if we don’t seize this opportunity to create an inspiring Waterfront neighborhood for people of all walks of life.

Seattle and the Northwest are focused on several values that, together, define our quality of life. Thoughtfully managed growth, economic vitality, environmental stewardship and a vibrant culture are among the keys to keeping our region a great place to live. Allied Arts stands with countless other civic and community organizations that believe our new Waterfront is the best opportunity we’ll have to maintain and enhance our region’s quality of life for the foreseeable future. We see the redeveloped Waterfront neighborhood as a place that will invite people to move into the city, serve as a stronger economic engine, provide more and better salmon habitat and act as a centerpiece for our arts and culture.

The community Waterfront Master Vision Collaborative was an effort to provide the inspiration to create a Waterfront for all. As civic and community groups interested in making a great Waterfront came together and communicated their interests to six teams of architectural designers, engineers and planners, a vision for Seattle’s Waterfront neighborhood was born.

Allied Arts is grateful to the countless people, organizations and government agencies that contributed their knowledge, time, funding and wisdom to this vision of the Waterfront neighborhood. We believe the ideas that arose through this Collaborative came from a synergy that is only achieved through an altruistic spirit, a desire to do what is good for the community and generations to come.

We also recognize and appreciate the work and public processes being led by the City of Seattle and the Washington State Department of Transportation. Because these governmental entities seek and are interested in civic input, the ideas that come from this broad array of waterfront stakeholders have social, environmental, economic, political and historic relevance.

The work of the Waterfront Master Vision Collaborative is not intended to be the final say in what changes should occur in the Waterfront neighborhood. Rather, it is a vision that meets the social, economic and environmental goals of a diverse set of concerned interests, and therefore dares to say, “It can be done—we can have a Waterfront for All.”

David Yeaworth, Executive Director

Sally Bagshaw, Waterfront Committee Chair

Laine Ross, President

Front Cover images, clockwise: Stephanie Bower, Michael Kimelberg, Scott Taylor and Via Suzuki, Matt Roewe

INTRODUCTION

When Allied Arts began recruiting architects and planners in late 2004 to participate in the Waterfront Master Vision Collaborative, virtually every person had the same question: “Didn’t we just do a Waterfront charrette for Allied Arts last year and another one for the City of Seattle this year—why do we need to do another?”

The answer lies in the decision-making timeline for the Waterfront. Three years ago our community needed to see freethinking, experimental ideas of what the Waterfront could be without a viaduct casting its shadow there. In December 2004, the City of Seattle and Washington State Department of Transportation officially announced that a cut-and-cover tunnel was their “preferred option” to replace the damaged viaduct. Subsequently, the Department of Planning and Development has crafted a “concept plan” which provides broad direction regarding the City’s intent for the redeveloped waterfront. Today, in 2006, it’s time to be more explicit. Permanent decisions will soon be made about where we’ll build parks, which streets will be our primary paths to the water, how we can improve salmon habitat and how we move people and freight along the waterfront.

Though scores of inspiring designs came from earlier charrettes, since the Nisqually Earthquake in 2001 no one had created one vision for the entire Waterfront that met the goals of the diverse group of Waterfront stakeholders and presented integrated uses for specific parcels of the land. This Waterfront Master Vision does both.

THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES OF THE PROJECT WERE :

Reconnect the Waterfront with adjacent neighborhoods

Create great places and activities for people

Improve marine habitat

Find diverse transportation means for people and freight

Expand affordable housing options

Enhance the Waterfront as an economic engine

Create a place that is true to the values of the Northwest

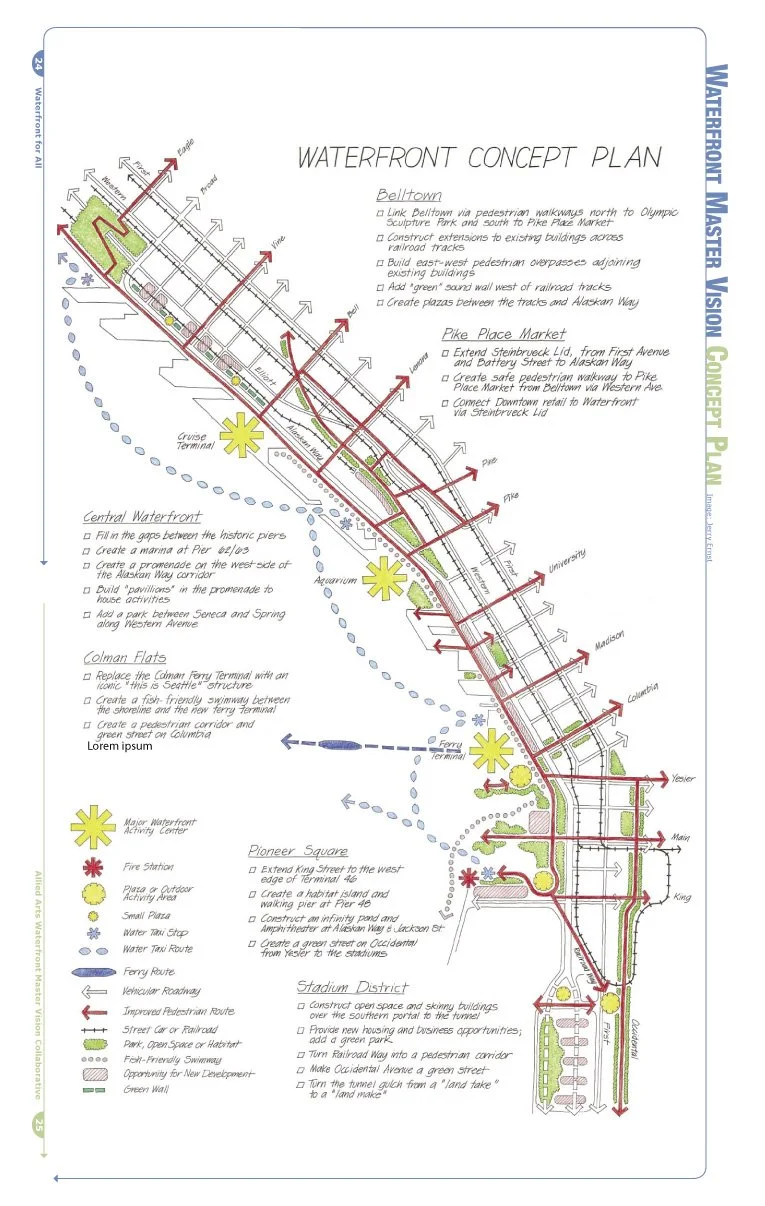

This report contains two main sections: Waterfront Concepts and Waterfront District Descriptions. The concepts segment provides a review of the major themes that arose across all sections. The district descriptions portray the Waterfront Master Vision in the six geographic sections through which they were conceived.

NEIGHBORHOOD CONNECTIONS

Create a South Portal Park above the southern tunnel portal

Turn Railroad Way into a pedestrian corridor

Extend King Street to the west end of Terminal 46

Create a boardwalk to “Habitat Islands” at Pier 48

Create a pedestrian green street at Columbia Street

Create a park and “viaduct ruins” at Seneca Street

Create a “plaza of the arts” at University Street

Create a pedestrian walkway from First and Battery, southwest to the Waterfront via Steinbruek Park

Build structures over the railroad tracks near Belltown with pedestrian overpasses attached

WATERFRONT CONCEPTS

As designers conceived the Waterfront Master Vision, key community values emerged and crystallized. Those values are summarized in five common themes. The themes are:

Neighborhood Connections

Open Spaces

Environmental Opportunities

Housing and Business

Transportation and Mobility

COMMUNITY VALUES

Reconnect the Waterfront to adjacent neighborhoods

Establish strong east-west pedestrian connections

Match the Waterfront to the flavor of the adjacent neighborhoods

FOR MORE THAN 50 YEARS , the Alaskan Way Viaduct has stood as a barrier between Seattle and its waterfront. Like a fence between the Center City neighborhoods and the water, the viaduct is a roadblock to paths that would lead people to the bay. To bring people to the water’s edge, the viaduct must be removed, and new pathways must be created.

Fortunately, the opportunities to link Center City neighborhoods with the Waterfront neighborhood are plentiful. The neighborhood connections that can be created between a post-viaduct Waterfront neighborhood and Seattle’s Center City—Downtown and the surrounding neighborhoods would improve the livability of the city as a whole as well as regenerate vibrant communities forvpeople throughout the region to visit. From the sports stadiums to Belltown, new pathways would work to re-connect Seattle to the water.

OPEN SPACES

WATERFRONT IMPROVEMENTS

Create a park over the southern entrance to the tunnel

Create a working waterfront viewing area and walking street on the north edge of Terminal 46

Create a boardwalk out to Habitat Islands at Pier 48

Create a grand promenade along the west side of the Alaskan Way corridor

Create a freshwater garden in between Piers 54 and 55

Create a “latte plaza” between Piers 56 and 57

Create a park between Spring and Seneca Streets at Western Avenue

Create a “Viaduct Ruins” at the Seneca off-ramp

Create a pedestrian causeway between the aquarium and Belltown at First Avenue and Battery Street

Create pocket parks and plazas next to a sound-wall due west of the railroad tracks near Belltown

Local residents feel passionate about upgrading the Waterfront neighborhood. They see green public spaces along the Vancouver, Portland and San Francisco waterfronts and ask, “Why not here?” As it is, Seattle’s Waterfront neighborhood is an auto-dominated, noisy area, inhospitable at night. Although it’s been this way for the past 50 years, there is hope. Beautiful, pedestrian- friendly open spaces will be the byproduct of the Alaskan Way Tunnel project. The message to our decision-makers is this: Create Waterfront destinations; give people reasons for wanting to visit the Waterfront by day and night; build restful, educational and romantic places for people to hang out; create space for shops and parks of various sizes; and provide interesting and safe places to walk or rest along the water’s edge

A central recommendation of the Waterfront Collaborative is to develop a substantial pedestrian promenade along the water’s edge. Rather than settling for a prettified sidewalk, the vision is for a wide, spacious promenade running from the two stadiums to the Olympic Sculpture Park, varied in landscape, dotted with places to sit and eat, accessible for wheelchairs and adjacent to new space for visitor-oriented businesses. This Waterfront Promenade would be lively 24/7—a place where visitors and residents can enjoy the changing seasons, admire the scenery separated from bike paths and cars, rent skates and sample good cheap eats or dine leisurely. The Waterfront Promenade would be a place for linking arms and family strolls, as it evolves into one of the world’s most awe-inspiring urban walks.

The reborn Waterfront neighborhood would offer quiet places for people to sit as well as plenty of places to connect with marine life, such as a quay where they could peer into a fish swimway and watch juvenile salmon make their way northward out of Elliott Bay. Friends will bring their dominoes, fetch a good cup of coffee and pass a few hours luxuriating in tales of old escapades, tasting a little salt brought by bay breezes. Lush green landscape, raised on berm, would provide elevated views of the grand sweep of the bay and mountains. Recaptured water from rooftops and streets would be channeled into filtration ponds and splashed into Elliott Bay through natural vegetation. Imagine inner-city waterfalls, and ones with an environmental purpose.

A fresh water garden on the pier invites passers-by to pause along the waterfront. Image: David M. Guthrie

While quiet areas would be offered throughout the Waterfront neighborhood, the experience as a whole would be one of energy, movement, tides, wind and people moving at various speeds. A human stream would come from the Olympic Sculpture Garden through Belltown on Western Avenue; people would descend grandly down the Steinbrueck Lid through a series of plazas, bringing the vigor of Pike Place Market to the front door of the aquarium.

Another form of energy and congregation would grow from the return of a concert venue to the neighborhood. The treasured “Concerts on the Pier,” formerly held at Piers 62/63 would return to the Waterfront at Pioneer Square. Here, a spectacular new setting—a floating, moveable barge—can be brought in and out as schedules dictate.

Seattle residents have longed for this stage along the Waterfront where human theater is the days’ entertainment. Ichabod Crane would meet Nine Inch Nails at the annual Halloween Walk. The Thursday night Art Walks can start in Pioneer Square, continue through the Central Waterfront, past Pike Place Market, right on into Belltown and to the Olympic Sculpture Park. People are captivating, and the sport of see-and-be-seen is timeless and authentic.

ENVIRONMENTAL OPPORTUNITIES

WATERFRONT IMPROVEMENTS

Create habitat islands at Pier 48

Build a salmon swimway between the ferry terminal and seawall

Create a stormwater treatment feature along Columbia Street

Create a stormwater treatment feature at the Pike Place Market

Create salmon habitat at Pier 67 by rebuilding the Edgewater Hotel and parking lot

Create a stormwater treatment feature at Vine Street

COMMUNITY VALUES

Increase salmon habitat

Filter non-point-source stormwater flowing into Elliott Bay

Provide opportunities for people to touch and see the bay

We have an enviable tradition in the Northwest of preserving forests, building public parks and protecting salmon and marine mammals. We value green over gray. WSDOT and SDOT’s viaduct and seawall reconstruction projects offer us a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to redesign Seattle’s front porch, and do good for our environment at the same time.

The Waterfront neighborhood has one of the most breathtaking natural settings in this country, and on this land our fore-bearers built a multi-lane concrete freeway. We have a choice. We can make the same decision a second time and rebuild an even bigger concrete structure, or we can take this opportunity to create a vital and environmentally friendly Waterfront—where native plants and trees, fish, marine mammals and people can thrive alongside the working waterfront while traffic flows smoothly out of sight. An authentic Waterfront should have clean water, plenty of parks and green spaces, enhanced marine habitat and a healthy Elliott Bay.

The waterfront is currently unwelcoming to fish and other marine animals. Juvenile salmon emerging from the Duwamish River into Elliott Bay have difficulty navigating to the sea because refuge areas are few. Habitat for many native species, including salmon, herons and harbor seals, has been compromised over the years. And access for people to the water is restricted almost all along Alaskan Way. hese problems can be addressed as part of the reconstruction project. Following the recommendations of local scientists and environmentalists, our vision includes habitat improvements such as a below-waterline seawall shelf, habitat islands and sheltered coves to dramatically improve the waterside of the seawall for marine life.

In the spirit of the Olmsted brothers, whose designs blended the best of the industrial city with beautiful landscape, we can build an inspiring urban environment within the working waterfront. People, marine mammals and fish would experience environmental benefits as a result of this waterfront redevelopment. Captured rooftop water and stormwater would be treated and guided into restful rainwater gardens, cascading fountains and creeks along dedicated pedestrian walkways. This scrubbed and screened water would be channeled into Elliott Bay, emulating natural freshwater inflows that are necessary to fish and marine mammal habitat.

Environmental enhancements would augment the great civic spaces. As suggested by University of Washington architecture students and botanists, native species of trees and plants would be planted along the water’s edge from Pioneer Square to the Olympic Sculpture Park, to provide shade, augment the food chain for fish, and create a “softened” landscape look. During the seawall rebuild, artificial shelves, protected coves, and daylighted quays would be added to provide shallow hiding spots and a continuous migration path for young salmon. People for Puget Sound urges a 30% increase in marine habitat “from lighthouse to lighthouse” around Elliott Bay. Marine animals and human visitors alike will appreciate the proposed habitat improvements where the water touches the land and people can touch the water.

HOUSING & BUSINESS

WATERFRONT IMPROVEMENTS

Create mixed-income housing on the tunnel’s south portal lid

Create a new ferry terminal that is both a transportation hub and a commercial center

Activate the Waterfront Promenade with small pavilions

Create small buildings on the Steinbrueck Lid for Pike Place Market-style shops and restaurants

Build pedestrian overpasses over the railroad tracks, linked to new buildings, in Belltown

COMMUNITY VALUES

Encourage people to move downtown to help meet growth management goals and create safe neighborhoods

Provide housing for people of all income levels

Augment the Waterfront as an economic engine

Maintain an authentic, local feel to businesses

When imagining the Waterfront without a viaduct, most people quickly see the opportunity to create great parks and plazas. Similarly, some people have a well-founded concern that public property should not be given to private interests and that access to it should be easy for all people, not just the well to do. Time has proven that the best public places such as the centuries-old Boston Commons or Vancouver, BC’s new waterfront are truly accessible to all people and incorporate a variety of activities nearby to make them safe, functional and inviting. Careful consideration must be given to the balance and integration of park space with housing and commercial areas in downtown Seattle as well.

Residential and commercial structures located strategically throughout the Waterfront neighborhood would ensure that it becomes a great place for residents and visitors. Without viable and growing businesses and residences nearby, parks and plazas could quickly become centers of undesirable behavior. Conversely, people who live and work near public places have the positive effect of keeping these places safe and lively, due to their “eyes on the space” and inclinations to use them.

Designers of the Waterfront Master Vision Collaborative recommend keeping all public land acquired from viaduct removal entirely in public hands, with the exception of the lids over the northern and southern portals to the tunnel.

Selling the air rights to the two- to four-block-long tunnel entrances would significantly pay for the construction of parks and plazas over the tunnel portals. Likewise, these two “land-makes” would both be safer and more livable areas with appropriate commercial or residential development.

TRANSPORTATION & MOBILITY

Prioritize space for pedestrians, bicyclists, and public transportation

Use public transit to link downtown neighborhoods to the Waterfront

Reactivate waterborne commuter transportation alternatives

Maintain a local freight corridor on Alaskan Way

Retain Alaskan Way’s pedestrian orientation--keep lanes narrow and speed slow

COMMUNITY VALUES

Prioritize space for pedestrians, bicyclists, and public transportation

Use public transit to link downtown neighborhoods to the Waterfront

Reactivate waterborne commuter transportation alternatives

Maintain a local freight corridor on Alaskan Way

Retain Alaskan Way’s pedestrian orientation—keep lanes narrow and speed slow

By moving the viaduct traffic below ground, this plan creates a blank canvas for a livable, walkable Waterfront neighborhood. Similarly, the Alaskan Way corridor would become more functional for bicycles and pedestrians.

NO AURORA ON THE WATERFRONT

Because the Waterfront neighborhood would be reconfigured as the viaduct is removed, some will argue that this is the chance to widen and increase the number of traffic lanes on Alaskan Way. To do so would relegate the Waterfront to little more than a downtown speedway, mimicking the six lane thoroughfare through some of our northern suburbs. The result would be to dedicate land for the automobile at the expense of pedestrians. As land-use decisions are made, assurances must be given by WSDOT and the City of Seattle that Alaskan Way will become no wider than its current configuration. The current layout of three to four traffic lanes should be retained to accommodate local freight and cars. Alaskan Way would keep its urban feel, with lanes no more than 10 feet wide just like the other Downtown avenues.

HURRY PATH AND WANDER PATH

Pedestrians use corridors if they are convenient, safe, expeditious and pleasant. The more people walk instead of taking their cars, the healthier we are as a society. This vision for the Waterfront would include both a “hurry path” and a “wander path” to enable people to choose to use the corridor as a quick means to a destination or for a leisurely stroll past other people, shops and marine habitat.

BICYCLE CORRIDOR

Currently, hundreds of cyclists use the Alaskan Way corridor every day as their primary route into and out of the city. Ample space would be given to bikes to ensure their safe use.

WATER TAXI

Seattle has a proud tradition of waterborne public transit. In the last century, a mosquito fleet of small passenger ferries provided by private and public contractors circulated around Elliott Bay. A new passenger ferry system that stops at new Waterfront depots would meet the needs of local commuters and tourists alike.

STREETCAR

Streetcars work best when they link neighborhoods to each other. Because the George Benson Waterfront Streetcar, which was mothballed last year, principally traveled north and south along Alaskan Way, its function was limited. Granted, tourists loved it for their occasional ride, but the new Waterfront Streetcar should benefit local residents at least as much as an average bus line. The objective should be to link Center City neighborhoods, including the Central District, the International District, the Stadium District, Downtown, Pike Place Market and Belltown to the Waterfront. Future links north to Ballard, south to SoDo, and east through the International District should be considered in the current plans. By moving the streetcar from Alaskan Way to a couplet on Western and First Avenues, and connecting the route to Seattle Center and the South Lake Union Streetcar system, the transportation linkages to all Center City neighborhoods would be made, and the Waterfront would become more accessible.

FREIGHT

The Waterfront neighborhood is an important freight corridor. Based on current data provided by WSDOT, 99.9% of all vehicles that use the viaduct today will be able to use the tunnel. The approximately 80 fuel-carrying trucks remaining could use Alaskan Way to connect to Ballard or South Seattle.

CENTER CITY SAFETY & TRANSITION PLAN

While Highway 99 is being replaced, several neighborhoods will experience severe transportation gridlock. West Seattle, Ballard, Greenwood and Green Lake residents will need alternative means to commute to and from Downtown. Seattle’s Center City Access Strategy and the coordinated efforts of Metro, Sound Transit and other transit agencies to increase bus service into and out of these areas must be completed before the viaduct is closed for good.

STADIUM DISTRICT

The Stadium District draws people from all over the world for sports and exhibitions, yet this area has poor connections to the rest of the city. The industry, heavy rail and freeway ramps that border this entertainment mecca on three sides discourage people from walking beyond the parking lots. Blocked by the viaduct and the Terminal 46 fence line, the neighborhood has no inviting connection to the waterfront.

Replacing the viaduct with a tunneled roadway will enable Railroad Way to become a scenic pedestrian corridor that links the two stadiums with the Waterfront neighborhood and the ferry terminal. In addition, Occidental Avenue, which is already a walking street on game days, would become a tree-lined green street dedicated to pedestrians, inviting people to stroll between Pioneer Square, the sports arenas and Exhibition Hall every day.

An urban design challenge is created at the southern portal of the tunnel where a moat-like gulch would separate the stadiums from the Waterfront. To solve this problem, the vision calls for a green lid to be built to arch over the gulch. Like construction successfully completed in Vancouver, BC, the lid would be engineered to provide open space for parks, residences and commercial retail. It would create space for “South Portal Park,” turning a “land-take” for cars and trucks into a “land-make” for people—the southern anchor in a Waterfront Promenade. Selling the air rights above the highway in a neighborhood that welcomes businesses, visitors and residents would partially offset the costs of creating a new residential neighborhood, and generate new property- and sales-tax income for the city.

WATERFRONT MASTER VISION CONCEPT PLAN

PIONEER SQUARE

WATERFRONT IMPROVEMENTS

Extend King Street to the West edge of Terminal 46

Create habitat islands and walking pier at Pier 48

Construct an infinity pond and amphitheater at Alaskan Way and Jackson Street

Turn Occidental Avenue from Yesler Way to the stadiums into a green street

Pioneer Square is the birthplace of urban Seattle. No Northwest neighborhood is more renowned for its eclectic mix of historic buildings, entertainment venues and art galleries. Though this historic district was founded because of its proximity to Elliott Bay, today the connections between Pioneer Square and the waterfront are poor. And if a pedestrian fords the asphalt river of Alaskan Way, there’s little of interest at water’s edge: only a fenced-off park at Washington Street Landing and a large rental-car parking lot.

Extending King Street to the west edge of Terminal 46 would create a well-defined border between the working waterfront to the south and the publicly accessible waterfront to the north. A new public space with a water taxi depot and public plaza would be created between Alaskan Way and the west edge of Terminal 46. The Waterfront fire station could be relocated from just north of the ferry terminal to the northwest corner of Terminal 46, providing quick, effective access for trained crews to both water and land emergencies. The firefighters would also provide “eyes on the street” 24/7. Other structures along this redesigned pier would include shops and restaurants that borrow from, and are in keeping with, the charm of Pioneer Square.

Nestled into the corner between the eastern edge of the new Terminal 46 and Alaskan Way, an infinity pool would serve as a wading pool in the summer and a skating rink in the winter. Around the infinity pool an amphitheater would be built for spectators to watch waders and skaters. A new home for the Concerts on the Pier would be created by a floating concert barge, which would dock next to the amphitheater. This appeals to many because the venue would be versatile and the barge moveable between scheduled events.

A pair of habitat islands could replace Pier 48, which is slated to become part of the over-water coverage of the new Colman Ferry Terminal. A boardwalk and natural vegetation would extend from Washington Street to the habitat islands, providing a healthy environment for fish and people alike.

Occidental Avenue would become a green street from Yesler to the stadiums, encouraging people to walk through the neighborhood. The famous “sinking ship” parking garage would become the headwaters of the Occidental green street with a new structure that offers an in-city waterfall and pocket park.

COLMAN FLATS

WATERFRONT IMPROVEMENTS

Replace the Colman Ferry Terminal with an iconic “this is Seattle” structure.

Create a fish-friendly swimway between the shoreline and new ferry terminal.

Create a pedestrian corridor and green street on Columbia Street.

By its nature as a transportation hub, the ferry terminal is a primary destination in Seattle. But did you know that Puget Sound has more ferry traffic than any other region in North America, and is second in the world only to Hong Kong? This calls for an icon that uniquely proclaims, “Welcome to Seattle! You’re here!”

Here’s what the Allied Arts design for the new Colman Landing Ferry Terminal proposes so far:

Car and truck traffic would go underground while waiting passengers are invited to a rooftop park with meandering paths and green space

Fewer cars and trucks would wait in holding queues because ferry traffic would use a reservation system rather than relying on a first-come, first-served approach

The grassy areas, with unrestricted views of the Olympic Mountains and Elliott Bay, would welcome ferry passengers as well as passing pedestrians into the rooftop park

Nearby, new docking areas for the water taxi would encourage speedy water commutes around and across Elliott Bay

Waterfront restaurants and business space would provide spacious new places to meet and dine in a Venice-like setting

The redesigned Colman Landing says “welcome and bon voyage” to salmon as well as people. Adding a 100-foot-wide saltwater swimway between the seawall and the ferry dock podium would create a canal that is romantic for people and nurturing to marine life. Pedestrians and kayakers could view the marine life from the city side of the new terminal. People could touch the waters of Elliott Bay on the south edge of the ferry site. Here, the ferry island would be graded to create a set of natural-looking tide pools and steps to the water’s edge.

Walking east from Colman Dock, pedestrians would find a green route into the central business district. With the Highway 99 on-ramp at Columbia Street removed, a new Columbia Street Plaza would become a light-filled space reserved for pedestrians. Here, amid downtown buildings, stormwaters from roofs and streets would follow a series of flowing waterfalls into ponds and swales to be cleaned naturally. The pathway would meander, creating areas of respite for pedestrians. Emulating natural coastal drainages, the water from Columbia Street Plaza would flow into the swimway, providing freshwater recharge that fish and marine mammal habitat require.

CENTRAL WATERFRONT

WATERFRONT IMPROVEMENTS

Bring people to the water’s edge by making pedestrian connections between Piers 54 and 55 and between Piers 56 and 57

Create a Waterfront Promenade on the west side of the Alaskan Way corridor

Build small pavilions on the promenade to house various activities

Add a park between Seneca and Spring streets along Western Avenue

Keep a portion of the Seneca Street off-ramp as a “viaduct ruin”

This portion of the Waterfront neighborhood is the heart of Seattle’s urban shoreline. Unfortunately, because of traffic noise, the dark shadows cast by the concrete stanchions of the viaduct, and the questionable safety of the area at night, the Central Waterfront lacks soul. The area currently has 11 lanes of traffic running over and through it, and hundreds of cars and trucks are parked all day and night under the viaduct. Even the preeminent piers 54-57 are often used as parking lots—piers 54 and 56 reserve space for private parking on or near their waterside ends. To add further disincentive to walk along the water, dumpsters and even cyclone fences block the perimeter walkways around many of the piers, which are legally public sidewalks.

The Central Waterfront should be the most public place in the city, with a wide variety of activities for people of all walks of life. Open spaces for picnics, play areas and lanes dedicated for runners, cyclists and pedestrians must be plentiful.

Seattleites and visitors alike are attracted to the pier sheds. Yet the appearance of private ownership of the public walkways around these structures often keeps people at a distance. Many storefront businesses along the water edges of the piers lack a consistent flow of pedestrians walking by, and therefore struggle to stay in business. Similarly, the Central Waterfront lacks real open space that would encourage locals to visit even briefly, let alone tarry for a while.

One solution to these problems is to link the west ends of the piers to create additional plaza space and create obvious public corridors. This new open space on the piers could be used for everything from outdoor theater to year-round gardens to seasonal outdoor restaurant seating.

Moving Alaskan Way to the east side of the corridor and shifting the streetcar line to Western and First avenues would enable construction of a wide Promenade along the water’s edge. Small pavilions would be placed every block or so to provide services and activities for visitors, such as coffee houses, bike and skate rental, tourist shops and a fish and chowder shack.

A new green park with space for frisbee players and spontaneous flag football games would replace the existing parking lot between Spring and Seneca streets along Western Avenue. This could also be a home for a small ecological interpretive center or community center.

It is broadly assumed that the celebrated brick buildings between Western Avenue and Alaskan Way, which today have their backs to the viaduct, will turn around to face the water once the highway is in a tunnel. To add more life and vitality to the neighborhood, apartments and condos within current zoning height limits and with street-level retail would be built in the five surface parking lots along Western Avenue.

PIKE PLACE MARKET

WATERFRONT IMPROVEMENTS

Create a pedestrian walkway running from First and Battery southwest to Alaskan Way at Pike Street via the Pike Place Market

Extend the character of the Market onto the walkway with small structures for restaurants and shops

Strategically encourage tall, skinny towers near the Market to help provide “eyes on the park”

Create a marina and quay at Pier 62/63

Pike Place Market is the number one tourist destination in the Pacific Northwest. Beloved by locals and visitors, The Market should provide an important link between Downtown and the Waterfront, but currently it does not. The walking connection is now discouraged by the noisy and shadowy concrete barrier of Highway 99; and the maze of hillclimb-stairways are confusing at best and dangerous after dark. The pedestrian connections and wayfinding between south Belltown and the Waterfront are awkward. These problems can be addressed making magical and safe connections from Downtown through the Pike Place Market to the Waterfront and from Pike Place Market north to the heart of Belltown on Western Avenue.

To revive connections and revitalize this area, a broad pedestrian causeway from Battery Street at First Avenue, a “grand descent”, could flow to the Waterfront via Steinbrueck Park at the Market. This “living bridge” known as the Steinbrueck Lid would cover Highway 99, providing pedestrian views, creating open space, and offering innovative opportunities for shops and affordable residential living.

Shops and residences along the western edge of the lid would be no more than two stories high and crafted with various design styles to create a neighborhood with character. Vehicles could access these structures from an alley in between the lid and the Waterfront Landing condos. Five narrow, residential towers, 12 to 16 stories tall, could be placed strategically on the eastern edge of the lid to invite more people to the neighborhood, yet be thoughtfully placed to retain views from established buildings to the east. By selling portions of the air-rights above the highway, this new Pike Place Market property can help to fund construction of the lid and work to activate the neighborhood.

The Market could use the plaza area of the lid as additional day-stalls for artisans and vendors. A water feature in the plaza would also serve as a system for storm water capture and treatment.

An additional advantage to this reconfiguration of the highway underneath the new Pike Place Market Plaza is that instead of rising over Elliott and Western Avenues as in the current designs, it would dip below these streets, surfacing roughly 60 meters into the Battery Street Tunnel. This redesign of Highway 99 creates an easier grade, readily attainable for trucks and cars going up hill.

BELLTOWN

WATERFRONT IMPROVEMENTS

Link Belltown north to the Olympic Sculpture Park and south to Pike Place Market with pedestrian walkways

Construct extensions to existing buildings across railroad tracks

Build east-west pedestrian overpasses adjoining existing buildings to new extensions

Add a “green” sound wall west of the railroad tracks

Create plazas between the tracks and Alaskan Way

The Belltown neighborhood is one of the Northwest’s fastest growing residential communities. It will become an even more popular destination neighborhood when the Olympic Sculpture Park opens to the public. Currently, a triple-wide swath of railroad tracks presents an imposing barrier between people and the waterfront. There are two sets of heavy rail tracks and one abandoned set of tracks formerly used exclusively by the streetcar.

Day and night, long trains stall pedestrian and vehicular movement between the Belltown neighborhood and the water. The tracks also create an unsightly blight on what is otherwise a people-friendly part of the city A lemonade-out-of-lemons solution is to construct a series of buildings or building extensions that arch over the tracks. The structures would provide new space for offices or studios over the tracks.

Pedestrian overpasses would be attached to the buildings along the southern or northern street side faces. These stairways and escalators would serve both as a means to walk over the tracks and as entrances to shops, cafes and offices above the trains.

Along parts of Alaskan Way an attractive sound wall—cushioned with growing plants fed by stormwater—would be positioned between the new building extensions to shield pedestrians from the noise of the trains. The three-sided spaces created by the sound wall and building extensions would become a string of pocket parks and plazas, offering areas of respite for pedestrians.

Together, the building extensions over the tracks, pocket parks, plazas and pedestrian overpasses would transform what is now a bleak and lonely part of the Waterfront into a vital new area of the city.

STREETCAR & WATER TAXI DIAGRAM

TUNNEL FUNDING

The Washington State Department of Transportation estimates that the core Alaskan Way Tunnel project has a 50% chance of costing under $3 billion and a 95% likelihood of costing less than $3.6 billion. According to WSDOT and City of Seattle sources, the City, state, federal government, and Port of Seattle have or will soon pledge more than $3 billion. With the addition of local and regional sources, as well as the possibility of supplemental funds from the federal government and Army Corps of Engineers, funding for the core tunnel project is essentially in hand.

PLEDGED REVENUE SOURCES

Gas tax $2.00 billion

Nickel tax $ .177

Previous State Allocation $ .016

City Contribution $ .015

Federal Transportation & Army Corps of Engineer Studies $ .008

Congress $ .231

Subtotal $2.447

PROBABLE SOURCES

Port of Seattle $ .200

City Light/SPU $ .300

SDOT $ .250

Subtotal $ .750

PLEDGED + PROBABLE = $3.197 BILLION

ADDITIONAL POTENTIAL SOURCES

Army Corps of Engineers

Tolls - High Occupancy Lanes

Local Improvement District

Harbor Maintenance Tax

Regional Transportation Investments

Future Federal Transportation Programs

Future Port of Seattle Investments

City Wide Neighborhoods/Parks for All Investments

GOVERNANCE & IMPLEMENTATION

STEWARD OF THE VISION

Civic projects blossom when inspired, well-qualified leaders have a mandate from the community to make an endeavor succeed. Fortunately, Seattle and the surrounding region have many capable leaders and much successful civic experience on which to draw. The cleanup of Lake Washington and saving Pike Place Market are two examples of civic-inspired projects with positive regional results. Within the past 10 years special-purpose governments have been created to design and build local desired amenities. Specifically, the City of Tacoma used a public development authority (PDA) to guide the redevelopment of its waterfront and within a decade, that city has been redefined. Similarly, a King County-created public facility district (PFD) built a stadium for the Seattle Mariners within five years from initial planning to the inaugural game. With appropriate legislative authority, a single-purpose government entity could also lead the redevelopment of Seattle’s Waterfront neighborhood. Both a PDA and a PFD have advantages of being entrepreneurial in nature and flexible to respond to the marketplace, yet transparent so that decision making must withstand public scrutiny. Public disclosure laws, competitive requirements and open public meeting laws apply. In other words, management of such projects is accomplished outside of a traditional bureaucracy, but is accountable to the public.

Other cities are using an alternative mechanism, a public-private partnership, to regenerate their waterfronts. For example, the Anacostia Waterway Initiative in Washington, D.C., brought together public agencies, non-profits, and companies in 2000 to share the goal of creating vibrant new places for people to live and work. The Anacostia initiative has generated a groundswell of interest in waterfront renewal in Washington, D.C., with impressive results. The river is substantially cleaner and previously run-down neighborhoods are beginning to thrive.

No matter which governing structure is ultimately selected, someone with optimism, energy, and the ability to communicate with a diverse set of stakeholders should be selected soon to oversee the Waterfront project and the many decisions that are being made right now. This “Waterfront Director” will need strong leadership skills, as well as the capacity to wake up every morning with the single focus of working to make the Waterfront the best neighborhood possible for all people.

DIVERSE BOARD

Redevelopment of the Waterfront neighborhood is a passion shared by a broad array of people and interest groups. Both the City’s Waterfront Partners Group and Allied Arts’ Waterfront for All coalition have representation from organizations that have not historically collaborated, yet are working together because they understand the importance of this rare opportunity to redefine Seattle and the Waterfront. These groups are models for the synergy that results when clear goals are held in common by diverse interests. Similarly, the Waterfront redevelopment authority should have a diverse board of directors that consist of motivated people who will prioritize their time to create a great waterfront. Recruiting capable people with passion will bring to the group the energy needed to make the project work. People with knowledge about urban design, cultural and environmental sustainability, transportation, finance and economics, construction management, legal matters and social services must be included.

Conclusions…

Capturing the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to create a Waterfront for All is the goal of a broad and diverse group of community organizations and civic leaders. And, recognizing that the Alaskan Way Viaduct has served as an important highway for over fifty years, a means to keep people and freight moving through the corridor is needed. The tunnel is the one solution that works to meet these goals.

Our final recommendations are these:

WATERFRONT FOR ALL

The Waterfront should be a great destination for people of all walks of life to enjoy, not an exclusive neighborhood for the rich.

PUBLIC LAND FOR THE PEOPLE

Public space gained from moving traffic into a cut-and-cover tunnel should remain in the public domain as parks and open space.

AN AUTHENTIC WATERFRONT

New development in the neighborhood should be authentic to Seattle, not a Northwest Disneyland or common shopping mall.

CONCURRENT LAND - USE AND TRANSPORTATION DECISIONS

Transportation and utility planning is currently far ahead of land-use decisions. Determining where to place parks, plazas, fountains and salmon habitat should be made in tandem with decisions about roads and utilities.

THANK YOU

Many thanks to our good friends and colleagues who made the Waterfront Master Vision Collaborative and this report possible. We want to specially recognize Jill Sterrett and her firm, EDAW/AECOM, for co-sponsoring the summer 2005 events, Jerry Ernst for facilitating the discussions and creating the overview drawing, and the designers and firms Via Suzuki, EDAW/AECOM, CollinsWoerman, Mithun, Weinstein A/U, Miller/Hull, Hewitt Architects, SVR, Pen & Pencil, GGN Ltd, Jeffrey J. Hummell Architects, Matt Roewe, Jeff Benesi, Stephanie Bower, David Guthrie, Brian Steinburg and Jane Yin for their vision and dedication. The illustrations in this report reflect hundreds of hours of volunteer labor and deep caring for the health of our community.

We also appreciate the generous donations made by the Guthrie Foundation, Cooper Newell Foundation, Seattle’s Convention and Visitors Bureau and the Cascadia Center, Discovery Institute. These organizations have helped us publicize the exciting ideas offered by the designers. We also appreciate the thoughtful guidance of Marcia Wagoner of PRR, Brad Kahn of Pyramid Communications and Kate Joncas and Anita Woo from the Downtown Seattle Association who helped us think strategically.

Lastly, we extend our appreciation to our many friends listed below who willingly offered their ideas and expertise to develop the vision of the Seattle Waterfront. Allied Arts appreciates the good work you do for our community. We thank you for your time and talents and your unflagging efforts to create the Waterfront for All.

DESIGNERS

Alan Hart

Amalia Leighton

Anindita Mitra

Annie Breckenfeld

Bill Hook

Brian Boram

Brian Court

Bruce Powers

Catherine Stanford

Chester Weir

Chris Saleeba

Christopher Wojtowicz

Dan Dingfield

Dave Rodgers

David Guthrie

David Spiker

Elizabeta Stacishin-Moura

Emily Pizzuto

Erich Ellis

Erik Hanson

Garteth Loveridge

Gordon Walker

Grace Leong

Graham McGarva

Ian Horton

James Thompson

Jane Yin

Jeff Benesi

Jill Sterrett

John Feit

Jon Szcesniak

Kanan Ajmera

Kathryn Gustafson

Kenneth McCarty

Krishna Bharathi

Lee Copeland

Lesley Bain

Marilee Stander

Mary Rowe

Matt Roewe

Matthew Roddis

Meriwether Wilson

Michael Kimelberg

Paul Byron Crane

Philip Davis

Richard Borbridge

Robert Hull

Roger Long

Shannon Nichol

Shawna Mulhall

Shoji Keneko

Sian Lewellyn

Stephanie Bower

Stephen Engblom

Steve Schlenker

Thomas Brown

Tim Bissmeyer

Tim Politis

Tom vas Schrader

Tonia Wall

Vaughan Davies

Yi-Chun Lin Stanley

ORGANIZATIONS

Argosy Cruises

Barbara Swift and Company

Belltown Community Association

Cascadia Center at the Discovery

Institute

CollinsWoerman

Cooper Newell Foundation

David Hewitt Architects

Downtown Seattle Association

Downtown Seattle Residents

Council

EDAW/AECOM

EnviroIssues

Feet First

Foster Pepper PLLC

Futurewise

GGL Ltd

Guthrie Foundation

Habitat for Humanity

Historic Seattle

Ivar’s

LMN

Martin Smith Inc

Miller/Hull

Mithun

NEA

NBBJ

Pen and Pencil

People for Puget Sound

Pioneer Square Community

Association

Port of Seattle

Preston Gates and Ellis

PRR

Queen Anne Community Council

SDOT

Seattle Aquarium Society

Seattle Department of Planning

and Development

Seattle Housing Authority

Seattle Parks Foundation

Seattle’s Convention and Visitors

Bureau

Seattle Steam

Shelly Brown Associates

Sustainable Seattle

SVR

Transportation Choices Coalition

University of Washington School

of Architecture

Via Suzuki

Vulcan

Washington State Ferry Service

Washington Water & Trails

Association

Watermark Tower Residents

Association

Weinstein A/U

WSDOT

EDITOR

Sarah Deweerdt

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Brad Bagshaw

Kristi Branch

Dan Dingfield

Joe Nabbefeld

Todd Vogel

WRITERS

Sally Bagshaw

David Yeaworth

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

Lara Dickson

THANK YOU

INDIVIDUALS

Aaron Ostrom

Amy Grotefendt

Anita Woo

Anonymous donors

Barbara Swift

Bert Gregory

Bob Chandler

Bob Davidson

Bob Donegan

Bob Pell

Brad Bagshaw

Brad Kahn

Brian Steinburg

Bruce Agnew

Bruce Powers

Chantelle Stevens

Chris Rogers

Christine Palmer

Christine Wolf

Dan Dingfield

Darryl Smith

David Allen

David Coleman

David M. Guthrie

David Levinger

David Vice

Davidya Kasperzyk

Debra Heesch

Dennis Fleck

Dennis Haskell

Denny Onslow

Diane Sugimura

Dick Sandaas

Don Welsh

Dorothy Bullitt

Einer Handeland

Elaine Spencer

Geri Poor

Gerry Johnson

Grace Crunican

Greg Easton

Greg Kipp

Guillermo Romano

Harold Taniguchi

Heather Trim

Holly Pearson

Jack McCullough

Jan Drago

Janet Stephenson

Jean Godden

Jeff Hou

Jerry Ernst

Jim Moore

Jim Young

Joe Nabbefeld

John Blackman

John Chaney

John Leonard

John Pehrson

John Rahaim

Jon Houghton

Jon Schorr

Josh LaBelle

Judith Whetzel

Karl Kruger

Kate Joncas

Katherine Casseday

Kathy Fletcher

Keith Cernak

Kevin Desmond

Kevin Stoops

Kristi Branch

Kristy Laing

Kurt Triplett

Laine Ross

Laura Cooper

Linda Mitchell

Lyn Tangen

Marcia Wagoner

Mark Isaacson

Mary McCumber

Matt Mega

Melinda Miller

Meriwether Wilson

Michael Cannon

Mickey Smith

Mike Mariano

Nancy Lucks

Nick Licata

Pat Davis

Paul Byron Crane

Paul Dziedzic

Pete Mills

Peter Hurley

Peter Steinbrueck

Philip Wohlstetter

Ralph Pease

Reed Waite

Richard Conlin

Robert Scully

Sally Garratt

Sarah Preisler

Shawna Mulhall

Sten Crissey

Steve Rowe

Susan Jones

Suzanne Skinner

Tayloe Washburn

Thérèse Casper

Tim Ceis

Tim King

Todd Vogel

Tom Graff

Tom Rasmussen

Tom Tierney

David Vice

Wendy Cox

Zander Batchelder